Bikeshedding (originally coined by C. Northcote Parkinson as the Law of Triviality) occurs when a development team spends a disproportionate amount of time and effort on a trivial or unimportant detail of a system, such as the color of a bikeshed.

This most often occurs because the supposed "trivial" detail is one of the few such things that everyone in the room actually understands.

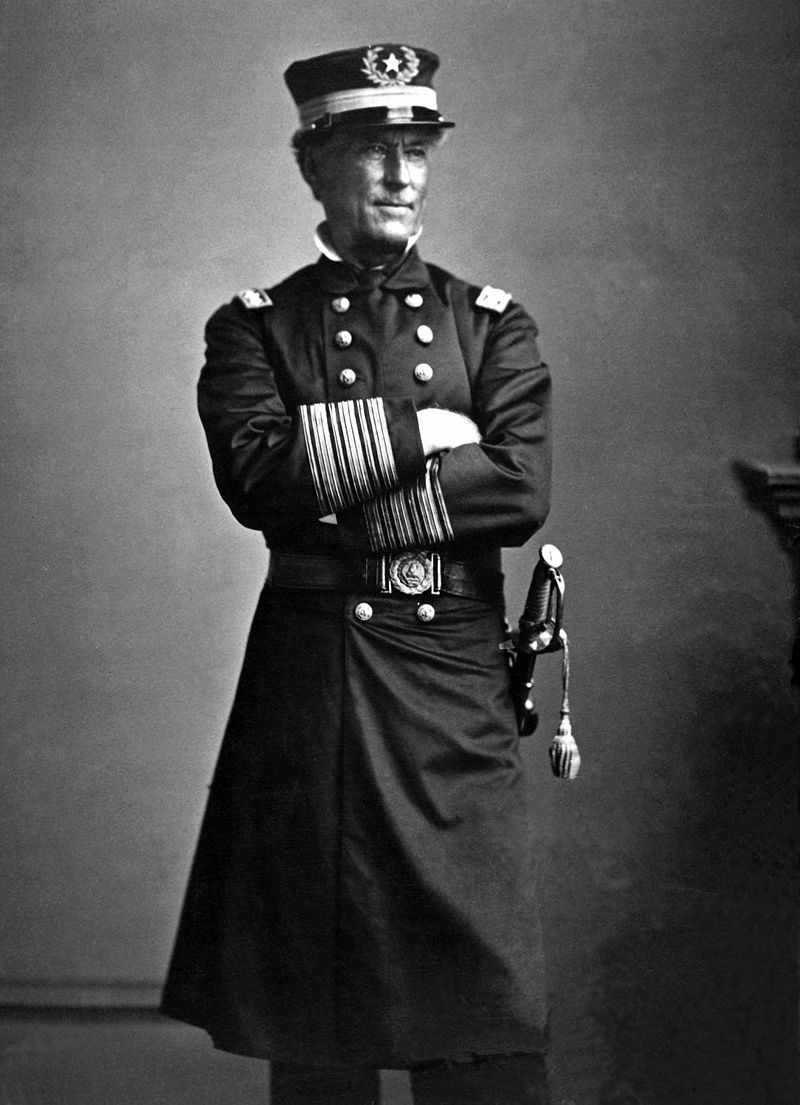

The solution is relatively simple, but scary: someone needs to be a dictator. Or, in our particular case, an admiral.

The Rundown

- Name: Bikeshedding

- AKA: Law of Triviality

- Summary: Spending disproportionate time on items with insignificant impact or little importance.

- Type: Management AND Methodological

- Common?: Can't we all just agree that <my opinion> is the best <opinion> for this?!

Tell Me a Story!

What follows is an expanded version of a story I tell in one of my speaking presentations.

A group of people are sitting in a room, tasked with an enormous job. The United States federal government has authorized the building of a brand-new nuclear power plant, and has assembled this group of individuals to design the best possible version of this new plant.

In this meeting we have a gathering of some of the greatest nuclear minds in the country: the fission and radiation expert, the transportation and logistics guru, the staffing director, the security captain, the finance lead, the operations manager, the disposal and waste professional, the CEO of the new plant. All of these are intelligent people, but intelligence is relative, and while they are experts in their fields, they may not be an expert in others.

(And if you work at a nuclear power plant and are thinking "This dumb blogger has no idea what we do," you are correct.)

The scope of this meeting is to determine what kinds of technologies can be included in this new plant. The fission and radiation expert starts off, saying that Technodroid controls and new titanium-alloy holding cells would be the most efficient way of storing unused uranium. The other people at the table look around, see that no one is voicing any concern, and agree to this expert's suggestion.

Now comes the staffing director, who states that, given the projected output of this plant, he'll need 50 people in each of the three shifts to run this plant efficiently. The group cannot find any fault with his argument, and so they agree.

On and on it goes, with each expert voicing their opinion on their field of expertise and how best to implement it, and the group (after a few minor concerns being voiced, perhaps) agree to each expert's recommendations.

This meeting is going very well, thinks the CEO. Just one person left. Unfortunately for him that one person is going to derail the entire meeting, albeit not intentionally.

See, the one remaining person is Sinjin, the "employee life" coordinator. Part of his job is to advocate for the personnel who will be employed at this plant, their perks, their working conditions, etc. And with one simple question, he can throw the entire meeting into chaos.

That question being, "Can we get a bikeshed?"

Now the staffing coordinator looks up from his laptop and says, "What kind of bikeshed?"

Sinjin, ready for this, says "One of the new glass-enclosed ones, so we can see what's in it. One with room for like 20 bikes. Maybe two, if there's budget."

The finance lead chimes in: "I think an opaque one would be better. Every bike shed I've ever seen was white or red, not glass. People won't know what it is at first glance."

Sinjin is now realizing that he has trouble on his hands. He's launched a conversation where, unlike what has been occurring up to this point, there isn't just one expert who can exert their will on the group; now everyone's an expert, everyone has an opinion, and they're going to voice it.

The meeting drags on. The attendees argue incessantly over what a bikeshed should look like, what color it should be, where it should be positioned, etc. The time spent on this $1000 bikeshed was the same amount of time spent on the multiple-million-dollar cooling equipment. And yet this thing, this one relatively-insignificant thing, is what took a well-functioning meeting and dragged it down to a chore.

The problem happens because, in this case, everyone was an expert. And the person who could have shut it down didn't.

Strategies to Solve

Bikeshedding can occur for lots of reasons, not least of which is having a "consensus" leader, the one who says things like "I need some kind of agreement before I can make a decision." Which isn't actually a decision, it's just forcing someone else to make a decision so you don't have to.

The solution to bikeshedding, for the vast majority of the causes, is for whoever is in charge to make a decision, and damn the torpedoes.

This is ultimately how bikeshedding stops, and indeed can be halted entirely; have a person who can make a decision.

In my experience bikeshedding arises from the confluence of three separate issues: people wishing to have input on a particular decision; said decision being understood by many such people; and the leader of those people being unwilling or unable to dictate a solution.

But what can you do if you aren't the leader? You can appeal to said person. Ask them to make a decision, force their hand. If you see bikeshedding happening, and want to stop it, this is most effective way of getting it done.

Summary

Bikeshedding occurs when a team or group spends a disproportionate amount of time on a trivial or non-critical issue. The solution is to have the "leader", whomever that is, make a final decision, before any more time gets wasted.

Have you been in a meeting where bikeshedding occurred? If not, why are you lying? If so, did anything get done about it? Share in the comments!

Happy Coding!